Wolf sounds can be incredibly colorful and a subtle change in loudness, duration, or rate of frequency in the sound can carry different messages for the wolf pack. Listen to this playlist and learn more about the fascinating world of wolf vocalizations below, as well as the wolves’ role in the ecosystem and mythology.

| #Title | Location | Ecosystem | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

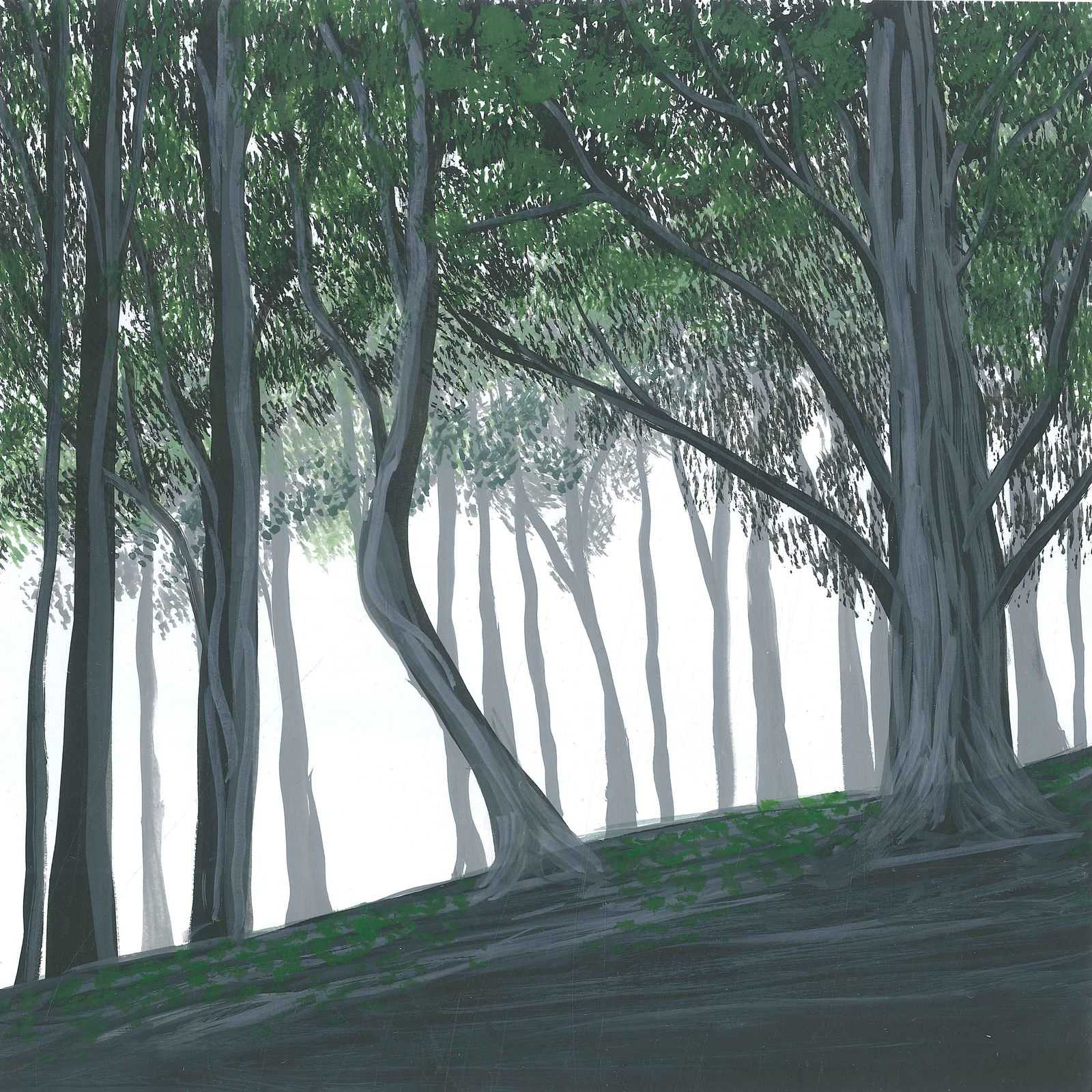

| Sweden | Temperate Forests | 04:38 | |

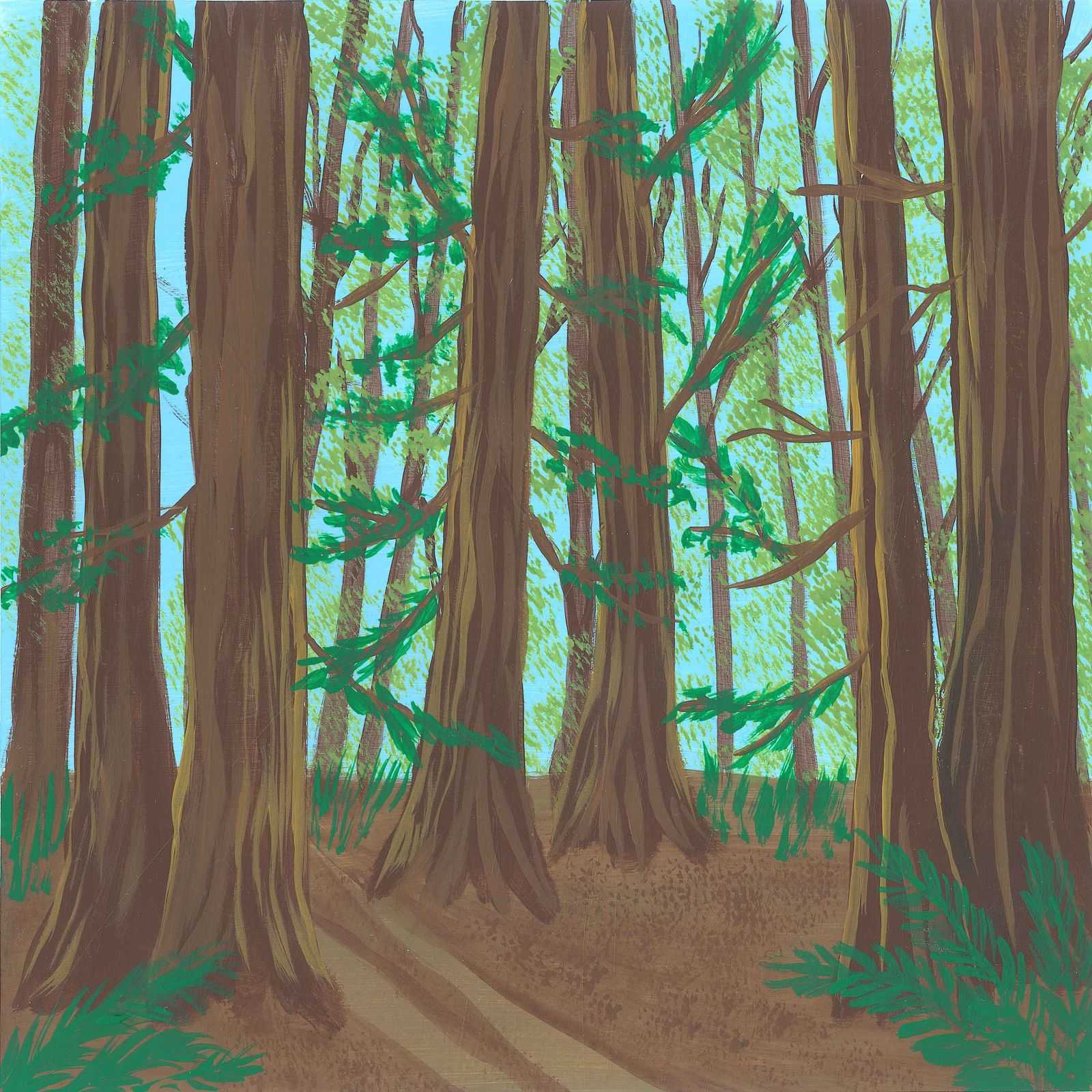

| Sweden | Boreal Forests | 01:33 | |

| Portugal | Temperate Forests | 10:54 | |

| Croatia | Temperate Forests | 01:20:31 | |

| Portugal | Temperate Forests | 01:03:57 | |

| Estonia | Temperate Forests | 00:50 | |

| USA | Temperate Forests | 02:38 | |

| Croatia | Temperate Forests | 51:30 |

Wolves use vocalizations to communicate, as well as body postures, scent, touch, and taste. “The wolf’s principal long-distance vocalization is the howl, which fits this rule as a lower-pitched, harmonically simple sound”, according to the book Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation by L. David Mech and Luigi Boitani.

What sounds do wolves make?

In the same book, Mech and Boitani write that the following wolf sounds exist:

- growls

- squeaks

- snarls

- moans

- whines

- yelps

- woofs

- barks

There’s also a changing state of wolves’ sound types, meaning changes in pitch, loudness, duration, or rate of frequency.

For example, a decrease in pitch or an increase in duration or loudness within growls may represent increased aggression.

Woofs and barks can also represent aggressiveness or assertiveness, as the wolf changes the muted warning call to a louder confrontational sound, explains Mech and Boitani.

Why do wolves howl?

While some evidence is speculative on this topic, researchers currently seem to agree that wolves howl because of the need for:

- reunion

- social bonding

- spacing

- mating

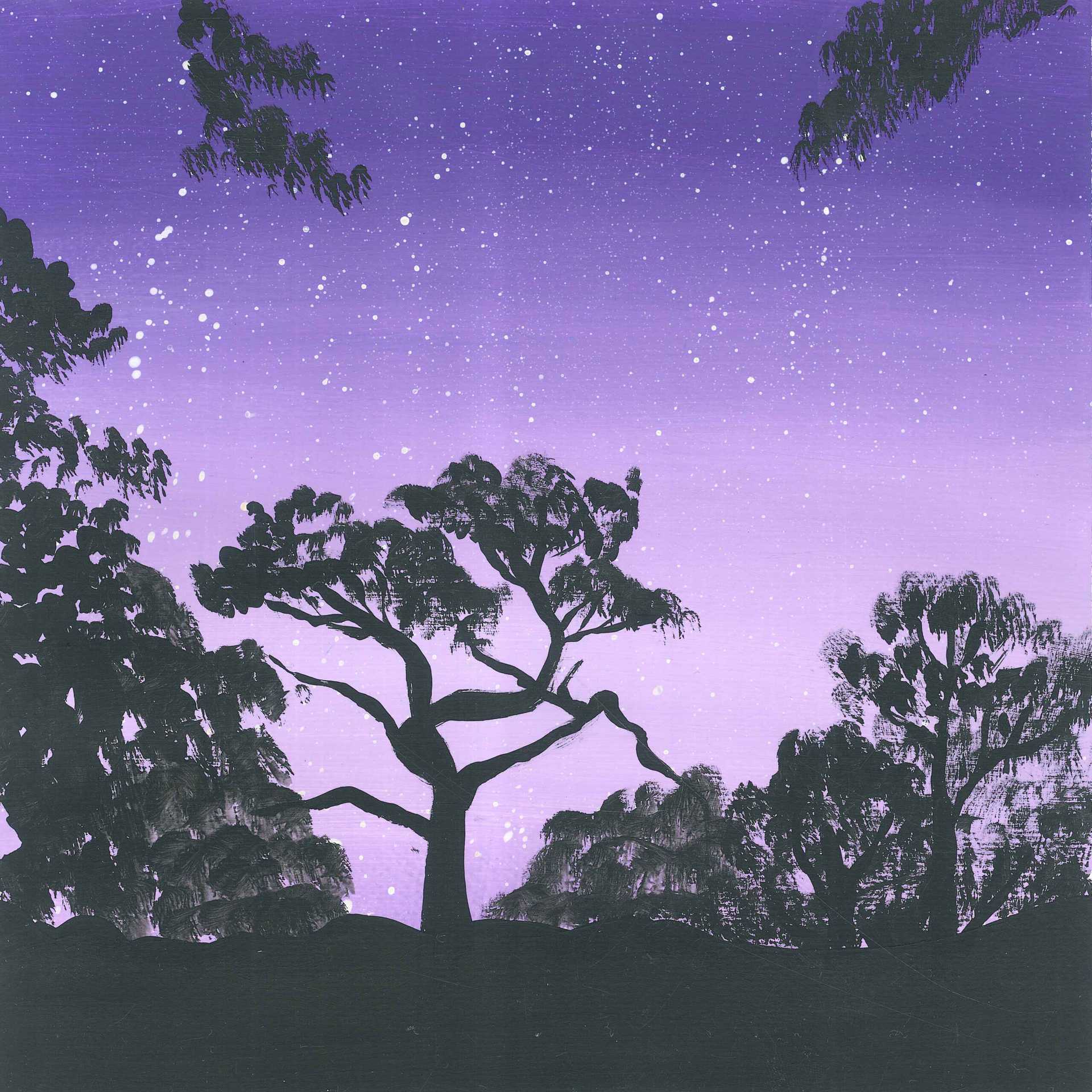

It’s also worth knowing that despite being a common belief, wolves do not howl at the moon and that the phases of the moon play no role in stimulating howls. Instead, they howl to, for instance, to find each other from a great distance or when in search of a mate (with which they bond for life).

Are wolf howls loud?

Yes, wolf howls are loud.

With a howl, a wolf can detect another member of its pack from 6 miles (10km) in a forested habitat, and 10 miles (16 km) on tundra, according to Mech and Boitani.

The fundamental frequency of wolves’ howls can range from approximately 90 Hz to 250 Hz (varying according to the age and size of the individual), and their harmonics can reach 11,000 Hz. We can also consider them to be quite loud to the human ear, especially the howls of gray wolves, which can reach a volume of around 90-115 dB (while a moderate conversation is 60 dB and a jet engine’s loudness is typically 130 dB).

Are wolf packs hierarchical?

Yes, but not in the way that you may have been led to believe. It is generally thought that wolf packs are structured around an alpha pair which dominates a ranked hierarchy of beta, gamma, and delta wolves, all the way down to a lowly ‘omega wolf’, and that individuals compete with one another for the role of leader.

This view of wolf behavior is derived from observations of wolves in captivity which were made in the 1940s by animal behaviorist Rudolf Schenkel; his paper Expression Studies on Wolves has remained a primary text on the subject for decades. However, as his conclusions were based on a group of wolves kept in an enclosure of just 656 square feet (200m²), they are being reassessed by modern research.

Wolf packs in the wild are more accurately understood as a group of offspring led by their parents. In 1947, Schenkel himself hypothesized that this structure may be true in the wild — yet it was the concept of the alpha wolf which gained popularity, possibly in part because of the existing acceptance of chickens’ ‘pecking order’.

These observations of aggression directed against others with a lower position in the social hierarchy, made by zoologist and comparative psychologist Thorleif Schjelderup-Ebbe in 1913, “had great influence on the whole view of science at that time, […] [and] was seen as an underlying dominance principle that structures society and behavior”, according to Ane Møller Gabrielsen, a senior research librarian at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, further work on wolf pack structure continued, like Schenkel’s, to draw conclusions from unrelated captive animals, making it equally suspect. The concept of alphas also came to influence dog training, justifying punitive methods on the basis that it was necessary for the human trainer to adopt the alpha role. (This has now been superseded by reward-based training.)

In 1970, The Wolf: Ecology and Behavior of an Endangered Species, by biologist David Mech, further popularized the concept of alpha wolves. However, by the turn of the present century, Mech had spent 13 summers studying wild wolf packs in Canada at close quarters. As a result, he published two articles attempting to update the popular understanding of wolf behavior: that packs comprise offspring that are led by their parents, and that, though a hierarchy does exist, (in that younger wolves are submissive to their parents), “Dominance fights with other wolves are rare, if they exist at all.”

Other observations of wild wolves also confound our expectations of animals with such a fearsome reputation: for example, wolf pairs are monogamous, often until death, and are so faithful that they generally stay within 330 feet (100m) of one another.

Are wolves beneficial to ecosystems?

The presence of wolves has many far-reaching benefits for the ecosystems in which they live and hunt. Yellowstone National Park, in the western United States, provides an excellent case study of these advantages.

Between 1914 and 1926, the 136 gray wolves living in the park were exterminated as a matter of government policy, extirpating the species from Yellowstone. This removal of the area’s apex predator brought about an ecosystemic collapse via a trophic cascade.

These indirect repercussions throughout a habitat were causing consternation among scientists as early as the 1930s. Effects included:

- A population explosion among elk due to decreased predation (as a result, between 1932 and 1968, the authorities were obliged to kill or remove more than 70,000 elk from the Northern Yellowstone herd; subsequently, harsh winters killed hundreds of elk because there was not enough food to support such a large population). Without predation, elk herds moved less, overgrazing brush and young trees, including ones upon which the beaver and songbird populations relied

- A population crash among beavers, with knock-on effects such as marshy ponds created by damming reverting to being free-flowing streams, causing heavy erosion

- The elevation of coyotes to the role of replacement apex predator, driving down the populations of their prey species and competitors such as foxes

- A reduction of food for scavengers such as ravens, magpies, eagles, and both grizzly and black bears, which subsist in part upon wolf kills.

Between 1995 and 1997, 41 gray wolves were reintroduced. Benefits included:

- A reduction of the elk population, leading to the restoration of aspen trees, the sprouts of which elk had been feeding upon indiscriminately. By lowering elk populations and removing weak and sick individuals, predation by wolves has made elk herds hardier, allowing them to better survive unpredictable conditions arising from the climate crisis, such as increasingly prevalent drought

- An increase of beaver colonies, from just one to 12, with resulting benefits for insects, fish (which regain cold, shaded ponds), amphibians, songbirds, and trees: beaver cutting produces healthy stands of willows (habitat for songbirds). Beaver dams and the ponds they create also even out seasonal pulses of runoff and store water which can recharge the water table

- A reduced coyote population and concomitant increases among antelopes and rodents

- An end to overgrazing, stabilizing riverbanks, and allowing rivers to recover and even to flow in different directions.

Since 2009, the wolf population in Yellowstone has fluctuated between 83 and 123; even such a seemingly small number has caused a complex ripple effect, one which continues to unfold, with untold benefits to the park’s ecosystems. And, in purely monetary terms, though the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone has cost around $30 million in total, wolf-based ecotourism brings in an annual total of $35 million.

Wolves in mythology and literature

Humans have been fascinated by wolves throughout history. We mostly admired and at other times feared them, but they are an integral part of mythologies around the world, nonetheless.

To mention a few motifs of wolves in mythology, the Ancient Romans connected the wolf to Mars, the god of war and agriculture, while the Greeks did the same with Apollo, their god of light and order. Romans also have a well-known tale of their city founders, Romulus and Remus, who were suckled by a she-wolf. From the North, we have the myth of a giant, fearful wolf, Fenrir, and Geri and Freki, pets of the god Odin.

In Chinese astronomy, the star we call Sirius is represented by the wolf that guards the heavenly gate, though the Chinese also associated the wolf with greed, cruelty, and mistrust. In Vedic Hinduism, the wolf symbolizes the night, while Tantric Buddhism says they live in graveyards and destroy corpses.

The indigenous people of North America consider wolves to be their relatives, and respect them for their strong individuality and the ability to also adjust to the needs of the pack or tribe.

In addition, there are also many mythological stories of people or gods turning into wolves. For example, Zeus turned the king of Acadia into a wolf; thus, and thus the first werewolf was born, according to other stories. Werewolves are also a common legendary species, especially in European folklore, but they also appear in Navajo stories, where it was believed that witches could turn into wolves.

In more modern times, we all know of the stories of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ and ‘The Three Little Pigs’, with the wolf as the evil antagonist character.

Wolves are shown in a much more positive light in Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, which has been also praised by wolf biologists for portraying wolves as caring, attentive families.

Although Kipling did a better job at depicting wolves more fairly and realistically than many before him, scientists agree that what wolves are still not doing is raising human babies.

We’re pretty sure that you love wolves -— since you are on this playlist page — but rest assured that humans and wolves are still not that close.

Earth.fm is a completely free streaming service of 1000+ nature sounds from around the world, offering natural soundscapes and guided meditations for people who wish to listen to nature, relax, and become more connected. Launched in 2022, Earth.fm is a non-profit and a 1% for the Planet Environmental Partner.

Check out our recordings of nature ambience from sound recordists and artists spanning the globe, our thematic playlists of immersive soundscapes and our Wind Is the Original Radio podcast.

You can join the Earth.fm family by signing up for our newsletter of weekly inspiration for your precious ears, or become a member to enjoy the extra Earth.fm features and goodies and support us on our mission.

Subscription fees contribute to growing our library of authentic nature sounds, research into topics like noise pollution and the connection between nature and mental wellbeing, as well as funding grants that support emerging nature sound recordists from underprivileged communities.