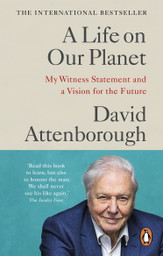

In 2020, at the age of 94, David Attenborough published A Life on Our Planet: My Witness Statement and a Vision for the Future – in his own words, “The story of how we came to make this, our greatest mistake, and how, if we act now, we can yet put it right.” In it, he tells the story of mankind’s impact on “the living world”, from his privileged position of someone who has traveled around the globe since the early 1950s making groundbreaking documentaries for the BBC. The book shares the insights of a man who has experienced the living world first-hand: “its greatest spectacles and most gripping dramas”.

As a young man, I felt I was out there in the wild, experiencing the untouched natural world – but it was an illusion. The tragedy of our time has been happening all around us, barely noticeable from day to day – the loss of our planet’s wild places, its biodiversity.

The book details Attenborough’s career in parallel with his most striking and memorable encounters with the natural world. He also integrates significant facts about the changes to the state of the planet which have occurred over the length of just one human life: his own. At times, it is heartbreaking.

One of the most impactful aspects of the book is the organization of the chapters in the witness statement section. These are named after years that have personal relevance for Attenborough. But, by also incorporating major global events that took place simultaneously, the chapters are turned into a combination of biographical notes, ecology lessons, history, and at times, solutions, too.

Eye-openingly, for each year, figures also show the global population, and the amount of carbon in the atmosphere and of remaining wilderness.

For instance: in 1937, when Attenborough was an 11-year-old searching for fossils in the east of England, believing that “the most important knowledge was that which brought an understanding of how the natural world worked”, the global population was 2.3 billion, carbon was at 280 parts per million in the atmosphere, and 66% of the world remained wilderness.

By 1968, the global population was 3.5 billion, carbon had reached 323 parts per million, and the amount of wilderness remaining had reduced to 59%. Fast-forward to 2020, to appreciate the scale of changes over the intervening 50-plus years: the global population had reached 7.8 billion; carbon was at 415 parts per million; and just 35% of the world was still wilderness.

In the chapter titled ‘1997’, Attenborough discusses “the largest habitat of all”, the ocean, and how we owe it everything, as that’s where life formed. In his meticulous manner, he takes us from early marine microbes billions of years in the past all the way to the blue whale, “the biggest animal that had ever existed on our planet” (which it took the Blue Planet team three years, in the late 1990s, to get shots of, cruising in the open ocean). But his account doesn’t stop here: he further discusses overfishing, starting with the 1950s, when commercial fleets first ventured into international waters. In largely unexploited seas, the catch was rich at first, but in a matter of years patches of ocean would be cleared of their fish stocks.

And so: “By the end of the twentieth century, mankind had removed 90 per cent of the large fish from all the oceans of the world.”

This illustrates one of our most damaging traits: not considering the long term consequences of our actions. “Targeting the seas’s largest, most valuable fish is exceptionally damaging. It not only removes the fish at the top of the food chain, such as tuna and swordfish, it also removes the biggest specimens within a population – the largest cod, the biggest snappers. In fish populations, size matters. […] So, by removing all the fish over a certain size, we remove its most effective breeders and soon populations collapse. In heavily fished areas, there are no longer any big fish.”

That’s just one chapter. Elsewhere, Attenborough recalls the “terrible decline” of other species, and habitats disappearing in front of his eyes – habitats that will likely only be available to future generations in documentary footage. From the coral reefs to the orangutans and the shrinking herds of the Serengeti, A Life on Our Planet shows us what the Earth was like, what is like now, and what it could be like in the future – both with or without action.

Each of us should compile our own witness statement. Anyone who loves nature and has been on this planet for at least a couple of decades has witnessed loss, extinctions, changes in seasons, and extreme weather events. I sincerely encourage you to do this, if only to remind less-attentive friends, family, lovers, and co-workers that the world is losing its life, and that there’s nothing natural about changes that should be measured in geological ages occurring within decades.

The notion of “putting it right”, and Attenborough’s vision for the future, shows theinspirational optimism of someone who, after almost a century on this planet, still has the energy to keep abreast of solutions to the accelerated degradation of the natural world (such as, rewilding and moving beyond growth).

The paperback edition of the book, published in 2022, includes an addition: ‘Why You Are Here’, a speech Attenborough gave at the opening of the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in November 2021. Towards the end of the speech, he mentions his hope for a “wonderful recovery” of the natural world in the lifetimes of generations to come.

We have the opportunity to create the perfect home for ourselves and restore the wonderful world we inherited. All we need is the will to do so.

It’s been three years since the book’s original publication – a long time in the Anthropocene, as we’ve learned by now. We’re still witnessing not only the ongoing degradation of the natural world, but the normalization of extreme weather events. Moving towards recovery seems demanding for a species “sleepwalking towards catastrophe”, perhaps because we want fast solutions – yet again, without understanding how our actions today are going to impact tomorrow. But maybe a clear understanding of what we are witnessing will help us move in the right direction.

“There are fewer fish in the sea today. We don’t realise that this is because of a phenomenon called the shifting baseline syndrome. Each generation defines the normal by what it experiences. We judge what the sea can provide by the fish populations we know today, not knowing what those populations once were. We expect less and less from the ocean because we have never known for ourselves what riches it once provided and what it could again.”

So, what is your witness statement?

Featured photo by Anca Rusu

Earth.fm is a completely free streaming service of 1000+ nature sounds from around the world, offering natural soundscapes and guided meditations for people who wish to listen to nature, relax, and become more connected. Launched in 2022, Earth.fm is a non-profit and a 1% for the Planet Environmental Partner.

Check out our recordings of nature ambience from sound recordists and artists spanning the globe, our thematic playlists of immersive soundscapes and our Wind Is the Original Radio podcast.

You can join the Earth.fm family by signing up for our newsletter of weekly inspiration for your precious ears, or become a member to enjoy the extra Earth.fm features and goodies and support us on our mission.

Subscription fees contribute to growing our library of authentic nature sounds, research into topics like noise pollution and the connection between nature and mental wellbeing, as well as funding grants that support emerging nature sound recordists from underprivileged communities.