Midnight Forest Frogs

Pacific Chorus Frogs or Pacific Tree Frogs, Pseudacris regilla, rank high among the hallmark sounds of North America’s West Coast. Their numbers reach peak density in the Pacific Northwest. Many know of them without realizing it through exposure in film, television, and other media. Their familiar “reek-keek!” and “karuck!” are THE Hollywood frog ribbits.

They may be found in dense populations numbering in the tens of thousands around a marsh, or they may be found solo wandering through a temperate rainforest like those found on the Olympic Peninsula. When solo wandering, they have a specific land call that feels like a sad, plaintive call for lost friends where none are found.

As they gather in a pod during mating season, males use two attractor calls to summon females. It’s not known why there are two, and there doesn’t seem to be a pattern as to their use. There are just two. Both are variations on that classic Hollywood sound. The first is a lower pitched monophasic “karuck!” or “ru-uck!” Two syllables are slurred into feeling like a single call. The other is a distinctly sharp, higher pitched two-syllable diphasic call, “reek-keek!”. If one should male start to encroach on another’s space, they switch to an aggressor call, a higher pitched, longer “kre-kre-kre-Kre_KRE-KREK!” call. Listening close to any chorus of Pseudacris regilla, and you will hear it sound out with distinction above the rest.

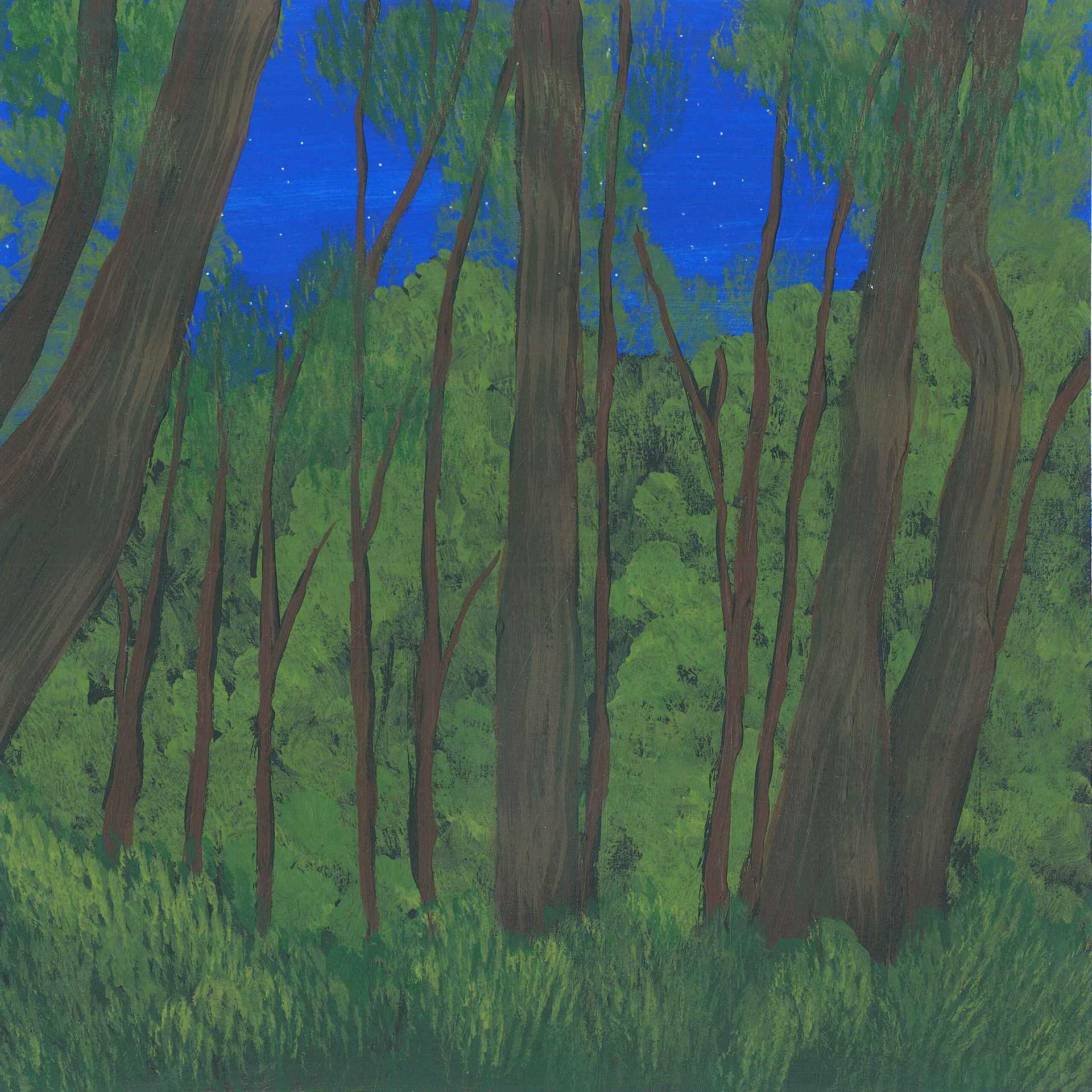

On the night of April 26, 2023, in Queets, one of the neartic temperate rainforests that flourish on the peninsula, I set up microphones near a transient water pool. When the snow really begins to melt out and the rains settle in late April, these pools collect among fallen logs and the bent roots of towering, moss-covered Sitka Spruce, Douglas Fir, and Vine Maples. I had been hiking near the confluence of Sam’s River and Queets River hoping to find elk on the move when I heard the faint whispers of frogs in the distance. I knew I had to take the opportunity to go listen.

I’ve sat among large masses of frogs around marshes in numbers so great that their tiny voices turned into a piercing roar that could drown out all other sounds. This was a small pod, though. Maybe a dozen frogs gathered around one of the vernal pools. With Pseudacris regilla, though, a dozen frogs may as well be a hundred once they start.

They move in and out of their chorusing in a cyclic fashion. It usually starts with one individual, bravely call out a lazy “Ka-rek!” Being the only voice is dangerous, leaving a the tiny animal spotlit by sound for any predator that might be around. If their call goes unanswered, they’ll eventually fall silent and use the quiet break to move away from this spot.

On this night I heard and saw several individuals sitting around the pool. As I set up the microphones for a long night of absentee listening, I heard the familiar monophasic “ru-uck!” One brave soul decided to test the water, so to speak. “ru-uck!” pause “ru-uck!” pause. Soon he was joined by a sharp biphasic “reek-keek!”… “ru-uck!” “reek-keek!” “ru-uck!” “reek-keek!” It didn’t take long for the rest of the pod to start up. I counted maybe six little croakers willing to give it go while I was still nearby.

It helped that I stopped setting the microphones and stood still, closing my eyes to listen to the party. “ru-uck!” “reek-keek!” “ru-uck!” “ru-uck!” “reek-keek!” Pseudacris regilla, like most frogs, have a rather poor sense of hearing. Their ears are tuned to their own calls and little else. It’s possible to have a full, normal-volume conversation with a friend without disturbing them. The moment you move, however, everything shuts down. These tiny creatures are incredibly sensitive to vibrations transmitted through the ground, through water, and through the plant stalks they may be clinging to. A simple shuffle of your feet is enough to put them on high alert. When a whole pod goes silent during the night, you can usually assume there is animal movement nearby or perhaps a leaf has fallen in the pool.

I finished setting up, hit record, and stumbled off. It was already well past sunset, and my flashlight was fading fast. There were still plenty of bent, knotty, slippery roots to clamber around before I got to the path. I made it back to my tent about a 30 minute hike down the trail and tucked myself in to bed, listen to more frogs coming out nearby. Around their voices was the soft pillowy sound of the distant rivers rushing.

It can be said that the four main rainforest rivers on the peninsula each have their own voice. Their glacier-fed waters traveling through deep-carved channels come alive in their reflections of the tall trees and canyon walls. The well-known Hoh is an old man, deep grumbling. Quinalt is like an energetic teenager, higher pitched and bouncing over rocks as it goes.

Bogachiel is more peaceful, quiet and luxuriant. Queets, where I am, is like a cougar. Tightly coiled, seemingly relaxed, but ready to spring hard the moment there’s a little rain, lashing out at those unprepared. This night, the cougar was relaxed, purring me to sleep while I listened to the croaking singing of these forest frogs.

This segment of the full recording starts on April 26, shortly before clock midnight, and finishes on April 27. It doesn’t quite make it to Solar Midnight at 1:14am, but we can’t have it all, can we?