How to organize your field recordings: A revised method

I’ve wanted to share my updated process for organizing recordings for a long while. A few years ago I wrote a two-part article about this crucial process; the positive feedback I received suggests that it helped a good number of people.

Subsequently, I’ve been on more field recording trips and have recorded much more in the region where I now live. I kept to those principles, following many of the same steps, but a few things didn’t work perfectly for me. Redundancy and rigid order (that either bored me or didn’t allow for fast delivery when needed) caused chaos between sessions and folders.

So, here, I’ll be describing an updated version. This article will deal with:

- Essential data

- Backups

- Folder structure

- Recording notes

- Creating an easy-to-understand digital audio workstation (DAW) session to use forever.

I also strongly recommend that you check out the excellent, broad range of information about these topics which has been shared by other pros with decades of experience. For example, Paul Virostek’s Field Recording: From Research to Wrap – An Introduction to Gathering Sound Effects is eye-opening in terms of thinking about and categorizing field recordings.

I’m working with the DAW Reaper and the audio repair tool iZotope RX – although in this method I am using it for navigating the file on the spectral display and add embedded data (the markers and regions).

OK – let’s go!

My first field-recording trip to the Atlantic Forest in Minas Gerais, southeastern Brazil, which rendered me hundreds of files. That’s when chaos ensued.

In the field

The biggest, biggest mistake one can make in the field is to forget to press the record button. The second, for me, is assuming that I’ll remember details like exact location, setup, microphone orientation, or date and time.

The way to solve that is to be very diligent with the file naming system directly on the recorder. So, if possible, I want the date and starting time to be on the recorded audio file, so there will never be any doubts about that. Therefore, I have these set before I reach the recording location. That means there’s no need to stress about it once I arrive – since, sometimes, it’s necessary to start recording immediately. There is no ‘solving it in post’ for this.

Then, once there: record a verbal summary of each new recording (slate). Just do that. I like to summarize how the soundscape feels, how my microphones are orientated, which technique I am using, gain, and high-pass filter (HPF).

Next: save the location’s coordinates in a list on Google Maps. I also like to snap a picture which usually also records the coordinates, if location is enabled; reiteration is no bad thing here. And I use a timecode in the local time of wherever I’m making the recording.

After the recording session

OK, once a recording has been made: backup.

According to my earlier method, I’d backup to a separate hard drive, leaving the files there untouched, only editing a second set of copies on a working hard drive. But, now, my first step is to copy the recorded files from the memory device to the working hard drive. I create a folder with a title in the form of ‘1_FR_Location Name_Original Files’. While those files are transferring across, I enter all the relevant details into a spreadsheet. For me, this includes:

- File name

- Date and time

- Length

- Location

- Coordinates

- Altitude

- Anthropophony

- Main species

- Ultra frequency content

- Picture file name

- Atmospheric conditions

- Decibel (dB) measurement

- Recording technique

- Gear used

- High-pass filter (HPF)

- Observations.

A mistake I’ve made a few times is to derive date-and-time information from the copies, instead of the original files on the SD card. The ‘creation date’ field of the folder browser gives the date of the creation of the copy, which is of course a very different story. I’m still paying the price for this with some older projects.

I can’t stress enough how important it is to enter this information immediately and thoroughly. It can be tedious, but it really is necessary.

If any recordings are only a few seconds or minutes long, or are absolutely useless, I delete them immediately. Having a clear cataloging system on a spreadsheet, and a sense of confidence in this method, means avoiding wondering, a couple of years later, whether I lost any files because the naming sequence seems to have gaps in it.

Listo! Now I have a clean backup and all the basic data I need. For me, this is already a cause for celebration. Hopefully it will be for you, too, because following these steps means dodging many headaches and avoidable, time-consuming work in the future.

In my previous method, I would now create another copy, in a folder with the suffix “-RX” – indicating that these files, once worked through, had been fully listened to, had had markers placed for species ID and to indicate cuts (say, for a vehicle passing by or similar disturbances).

However, I’ve come to the conclusion that this isn’t the best idea. I was trying to be a purist by editing out anthropogenic noise and retaining only ‘pure nature sounds’. I now think differently (a subject for another article, perhaps), but I no longer want to make any cuts to the files I’m working on.

Therefore, instead of going through each file first in noise removal/audio cleanup software iZotope RX, I create a session on my DAW (I use Reaper) and send all the files there. Then, as before, I organize them by date, placing them in a 24-hour timeline.

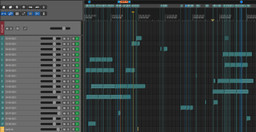

The image above shows that I have one track for each day of recording, organized chronologically, with each audio file starting at its original starting time. The markers on top stay at the start of the file, and their ID number corresponds to the number allocated to each file in the numbering system.

The color scheme is also helpful: the original material – both the audio clips and their markers – have one color (in this case, green). Later, the regions exported to different platforms or projects are also allocated their own color. I find that this is the best way to keep track of what I have done with specific audio segments – which I find particularly important in the long term. Sometimes – if I’m asked for exclusive material, or I want to diversify what I publish across SoundCloud and Earth.fm, or what goes into my Bandcamp albums – with the region system, a track is assigned to each of these platforms (for example, Earth.fm in yellow at the bottom of the track list). But more on this later.

Once all the tracks are displayed in the session, in a beautiful and orderly way, I open each one in iZotope RX, which is set as my secondary editor on Reaper.

And now, yes, it’s time to listen to each file in full and place markers and regions. I have only two rules: regions for noise (planes, vehicles, maybe me sneezing in the distance) and markers for species ID. I do this because markers and regions are shown with different colors on Reaper’s audio clips, which helps me better navigate them.

Simultaneously, I use a notebook and a pen to take whatever notes I find useful. I generally focus on subjective elements such as a particularly beautiful passage, or an impressionistic moment like an outstanding reverberation or interesting tonality. Since I consider what I do as being closer to sound art than to an archive of field recordings, I let myself be guided by these felt impressions – but I may also take note of the loudness and dynamic range.

To be clear: I don’t do any processing at this stage, just add the time-stamped information.

Only once the file has been thoroughly listened to, and the necessary notes have been made, do I copy it to the relevant folder in my ‘Field Recording Originals’ hard drive. This guarantees that each iteration of the recording file will contain all this data.

As you may be aware, this process could take several days. But what you recorded last week may contain material you want to use immediately, before you’ve been able to listen through in detail or started to ID species. In this case, your DAW session already has all the audio clips laid down nicely, meaning you are able to mark what you’ll take right now. And, at any point, you can listen to that file again and make the necessary notes without having to go back and forth between Izotope RX and Reaper.

‘01_FR_Andalusia_originals’ is the folder where the original files go immediately, and which changes are saved to after taking time-stamped notes from the file itself.

‘02_FR_Andalusia_ID’ contains the snippet I export from the original file in order to submit it to BirdNET, or show it to someone who’s able to help with species identification. These recordings are identified with track names the same as the original, but with the addition of “ID-nr”. Once species have been correctly identified, I add their names to the end of the file – and to the marker on iZotope RX – so I always know where it came from and that each instance is identified. Too many loose ID snippets meant that I no longer remembered which bird it was. In the end, it might also serve as a mini-catalogue of species I wasn’t then familiar with.

‘03_FR_Andalusia_session’, of course, is where the files from the Reaper session goes, along with all the backup and peak files.

‘04_FR_Andalusia_exports’ usually contains subfolders for the platforms, projects, or clients I’ve exported files to.

This system is pretty simple, but does allow some finesse.

Editing

Now, let’s go back to the DAW session and look in more detail at how I handle audio clips there.

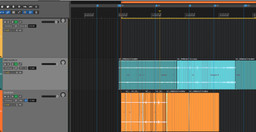

The main idea is that the original audio files don’t suffer any direct editing or destructive processing. Keeping them intact means that it’s possible to go back to them at any point. To ensure this, I create an adjacent track for the purpose intended (let’s say, an export to SoundCloud). This new track will simply be copied from the audio clip above, in order to make my edits without affecting the main track. The image below shows how I use a region at the top to establish the length of what has been used from a recording and the edited clips below.

Even if I would prefer to transfer chosen segments/tracks to a new session – as in the case of my last album – I will still mark with regions what has been taken from the original set of recordings.

And that’s it! Even if it’s a time-consuming process, it now flows much more smoothly, takes up less space, and is a bit more fun to work with. This approach feels much more comfortable.

Thanks so much for reading – please let me know if you have any thoughts or suggestions.

Earth.fm is a completely free streaming service of 1000+ nature sounds from around the world, offering natural soundscapes and guided meditations for people who wish to listen to nature, relax, and become more connected. Launched in 2022, Earth.fm is a non-profit and a 1% for the Planet Environmental Partner.

Check out our recordings of nature ambience from sound recordists and artists spanning the globe, our thematic playlists of immersive soundscapes and our Wind Is the Original Radio podcast.

You can join the Earth.fm family by signing up for our newsletter of weekly inspiration for your precious ears, or become a member to enjoy the extra Earth.fm features and goodies and support us on our mission.

Subscription fees contribute to growing our library of authentic nature sounds, research into topics like noise pollution and the connection between nature and mental wellbeing, as well as funding grants that support emerging nature sound recordists from underprivileged communities.