In search of natural silence in the Anthropocene

The day will come when man will have to fight noise as inexorably as cholera and the plague

Robert Koch (1905 Nobel Prize-winning bacteriologist)

In 2014, BBC Future – a platform for “evidence-based analysis, original thinking, and powerful storytelling” – published a piece titled ‘The Last Place on Earth without Human Noise’. The article (one of a Last Place on Earth series) set out to discover whether anywhere on Earth was entirely free of anthropophony, and was inspired by the release of Zero Decibels: The Quest for Absolute Silence, a memoir by “novelist, teacher, [and] ex-lobsterman” George Michelsen Foy.

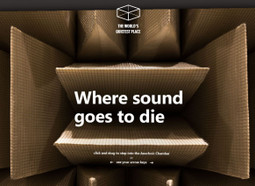

Pushed to breaking point by the literally deafening din made by New York Subway trains, Foy embarked on a quest for “the grail of total quiet”, which took him to the catacombs of Paris; one of the soundproofed “vaults” that Joseph Pulitzer retreated to due to acute sound-sensitivity; and even a mile below ground in a Canadian nickel mine. He even braved Orfield Laboratories’ anechoic chamber, a space ‘free from echo’ because it “absorbs 99.99 percent of sound”. (Until 2015, when Microsoft took the crown, it was declared “the quietest place on earth” by Guinness World Records.)

Sound levels in a quiet night-time bedroom might measure 30 decibels (dB); by contrast, the chamber reaches levels of -20 dB. As appealing as complete silence might seem in theory, the reality is a different matter: “No one has ever endured even forty-five minutes alone in its pitch-black interior”. In that space, people are “tortured by the eerie sounds of their own body”; the beating of the heart, gurgling of the stomach, and inflation and deflation of the lungs become the ears’ only point of reference, to the extent that, since the standard sounds of standing or walking are no longer audible, “perception becomes skewed, and balance and movement become almost impossible feats”.

This somewhat nightmarish ordeal is a far cry from what we think of when we rhapsodize about the peacefulness of the countryside or the pleasure of undisturbed sleep.

So what do we mean when we talk about ‘quiet’?

It’s instructive to consider the boundary between pleasant (or at least neutral) ‘sounds’ and less welcome ‘noise’. Think of disruptive noise and you’re likely to imagine the outcomes of human activity: traffic, sirens, pneumatic drills, low-flying aircraft – among other examples. Do any naturally occurring sounds tip over into the category of noise? Birdsong, babbling brooks, and lapping waves are among the sounds that we are most pleased to experience. Even those natural sounds which have their detractors – say, cicadas, thunder, or seagulls – will have an equal number of supporters. The same, alas, cannot be said of a blaring car alarm.

In which case, the sonic appeal of natural settings is less to do with their sound levels that the specific types of sounds which are present: calming rhythms like the animal and bird calls, the drone of bees, the rustle of leaves and the creak of branches in the breeze, the trickle of streams; sounds which humanity has become habituated to throughout its entire existence.

Where can we go to hear natural sounds away from human noise?

Tragically, locations where the human-made noises of planes, boat engines, and industrial processes do not intrude are few and far between. It’s eye-opening to hear regions which might be assumed to tick that box being discounted. Antarctica, for example: a polar desert fringed by colonies of seals and penguins might be assumed to be pretty tranquil. Yet, on the contrary: “In the summer, research planes and tourism boats are prevalent, and resident scientists power their camps with whirring diesel generators, the rumble of which can be heard for 20 miles or more around.”

In fact, the BBC article quickly dismisses the notion of the natural world existing in some sort of immaculate aural bubble untainted by anthropogenic noise. Soundscape-ecology pioneer Bernie Krause states that, “There are no places on Earth that I’ve been that haven’t been affected by human sound”, while acoustic ecologist and sound recordist Gordon Hempton has “recorded sounds from one or two aircraft per hour” in even the depths of the Amazon rainforest – 1,200 miles (1,900 km) from the closest city. As he points out, “Even if you are far from a road, you are not far from the roads in the sky.” (Hempton, who believes that ‘natural silence’ “might be on the verge of extinction”, is featured in two short documentaries on earth.fm’s rundown of soundscape ecology on film.)

If nowhere in existence is entirely free from the incursions of human noise, the question becomes, ‘Where are these incursions least frequent?’ To answer this question, we can also ask:

Can natural quietness be certified?

Hempton works to identify areas of around 1,200 square miles (3,100 square kilometers) or larger – “enough to create a sound buffer around a central point of absolute quiet” – which remain human noise-free for 15 minutes or more at a time. Over 30 years, by 2014, his list had diminished to just 12 examples within the US – the locations of most of which he, understandably, kept under his hat. However, some of them make his top picks for “the rarest […] soundscapes in the world”, which are available at the bottom of this article and also includes locations in Taiwan, Namibia, and Poland.

As co-founder of Quiet Parks International (QPI), Hempton is responsible for the certification of Wilderness Quiet Parks, Urban Quiet Parks, Quiet Trails, Quiet Conservation Areas, and (soon) Quiet Marine Parks, with the aim of certifying “roughly 50 Urban Quiet Parks around the world in coming years”, to “offer natural beauty and inner stillness on a daily basis”.

These certifications have benefits beyond offering a corrective to effects from noise pollution on humans that range from “stress and sleep disturbances to high blood pressure and heart disease” (among many other insidious health burdens); this is due to the fact that abrupt noises are subconsciously interpreted as signs of danger and therefore “trigger involuntary fight-or-flight responses […] [which] strain [the] autonomic nervous and endocrine systems”. The certifications also counter the interference of noise pollution upon “animals’ abilities to hear important sounds, like birdsong, and to fundamentally alter where animals live and their reproductive fitness”. In addition, soundscapes free from noise pollution are valuable indicators of healthy habitats. As Hempton says, “When we find places on planet Earth that are relatively free of noise pollution, we also find the healthiest places.”

When we find places on planet Earth that are relatively free of noise pollution, we also find the healthiest places.

Other concrete outcomes from the organization’s work has led, for example, to the Indigenous Cofán people in Ecuador – whose land was designated QPI’s very first Wilderness Quiet Park – being able to produce the finances necessary “to defend their land from illegal gold mining”, through ecotourism. The Cofán number “about 1200 people today, down from estimates of 30,000 [but] as they fight to preserve their land, they are now able to export quiet—a sustainable natural resource.”

Kenya Williams, an advisor to QPI, believes that its certifications ultimately alter “behaviors, much in the same way people have learned about the importance of recycling through education and awareness” – part of a cultural shift required if people are to “value and steward quiet in urban areas”.

There is some way to go, but hopefully initiatives such as QPI will continue to push towards legislation which would protect quiet areas, in a way equivalent to dark sky programs. (Existent legislation includes the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs’ Noise Action Plan: Agglomerations (Urban Areas), which “include[s] provisions that aim to protect existing quiet areas from an increase in noise”.)

Other organizations doing their bit include:

👉 Quiet Mark, a charity which “campaigns for quieter products, whether they are airlines, trains, hair-dryers, food-mixers or even musical instruments”, on the basis that “products are noisy […] because it is cheaper to make them that way”

👉 DREAMSys (Distributed Remote Environmental Array and Monitoring System), “a project to develop a new measurement-based approach to environmental noise monitoring and mapping” – rather than one based upon prediction.

A final irony: in 2006, the Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE) attempted to prompt legal protections by visually mapping tranquility in the country, as a way of enabling the relevant authorities to preserve it. Its definition of tranquility constituted “a natural landscape, the sound of birdsong, the absence of man-made noise, woodland, and a clear view of the night stars”. On this basis, CPRE named an area in Northumberland as the country’s most tranquil location. However, the reason for this was its location… alongside a military training area. “Away from all roads and accessible only by foot or mountain bike, that corner of the country is indeed very silent – except when tanks are rumbling across the base and soldiers are practicing on the firing range.”

If you plan to visit and glory in the sounds of nature, time your trip with care.

Further reading:

▪️ ‘Gordon Hempton: Silence and the Presence of Everything’ (podcast interview and transcript)

▪️ ‘Building a Movement to Preserve Silence as a Natural Resource’.

Earth.fm is a completely free streaming service of 1000+ nature sounds from around the world, offering natural soundscapes and guided meditations for people who wish to listen to nature, relax, and become more connected. Launched in 2022, Earth.fm is a non-profit and a 1% for the Planet Environmental Partner.

Check out our recordings of nature ambience from sound recordists and artists spanning the globe, our thematic playlists of immersive soundscapes and our Wind Is the Original Radio podcast.

You can join the Earth.fm family by signing up for our newsletter of weekly inspiration for your precious ears, or become a member to enjoy the extra Earth.fm features and goodies and support us on our mission.

Subscription fees contribute to growing our library of authentic nature sounds, research into topics like noise pollution and the connection between nature and mental wellbeing, as well as funding grants that support emerging nature sound recordists from underprivileged communities.