Following our reviews of David Attenborough’s series Wonder of Song and Secret World of Sound, and of his book A Life on Our Planet, we’re revisiting one of the beloved presenter’s most extraordinary achievements of recent years: 2022’s The Green Planet.

Recapitulating The Private Life of Plants (1995) and Kingdom of Plants (2012),The Green Planet benefits from advances in filming technology that make it possible to show more fully – and more strikingly than ever – the extent to which plants move. Sped up with time-lapse photography shot on specially designed camera rigs, it’s astonishing to see plants behave in ways that we tend to imagine are the sole preserve of animals. While they may not be able to move freely from place to place, watching the tips of their stems creep towards light – or twine around those of competitors’ – and their flowers follow the movement of the sun, makes clear their responsiveness and reactivity to their surroundings.

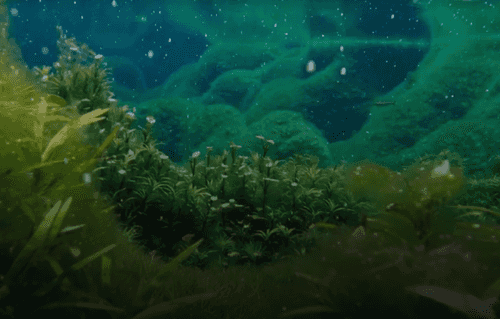

Across five episodes, the series explores tropical forests (home to upwards of two thirds of the world’s plant species – a situation which, naturally, leads to intense competition); aquatic environments (a hidden world of beautiful and bizarre habitats); and plants’ adaptations to both seasonal changes – including the importance of exact timing in the context of often extreme environmental fluctuations – and to the harshness of deserts (with their extreme temperature changes and water scarcity). And in the final episode, the relationship between humans and plants is put under the microscope, with an emphasis on the negative environmental effects that have resulted from human development, and the ways in which plants have had to accommodate these changes. Episode five also examines the creation of green spaces in urban settings and the promotion of environmental responsibility.

But it isn’t only plantlife taking a starring role, but fungi too, with bioluminescent ‘chimpanzee fire’, growing in Congo, releasing uncountable billions of spores – while, elsewhere, another fungus controls leafcutter ants with chemical signals that compel them to fetch specific types of leaves.

Plants are, after all, our most ancient allies, and together we can make this an even greener planet.

It’s also notable that blockbuster natural history series of this type are, as Variety notes, more “willing […] [than ever] to put uncomfortable truths regarding environmental damage alongside feel-good shots of beautiful beasts and pristine landscapes”, with environmental narratives “routinely [being] ‘bake[d] in’”. The challenge of calibrating a perfect balance between environmental messaging and a sense of “being told off” is one which Attenborough has long been mindful of. Yet it is a balance that he has perfected, avoiding a “hectoring” tone by instead prioritising “a narrative of hope”.

Attenborough’s palpably genuine delight at his close encounters with the natural world is itself part of that recipe, which has been refined over the course of decades. Even after having made natural history programmes, at this point, for just shy of 70 years, he’s evidently thrilled when a bat appears to drink nectar from a nearby flower while he’s delivering a link; it’s this unshakeable, deeply-felt joy and fascination which is his greatest gift to the viewing public.

That such a “passion project” turns his joyfulness, curiosity, and fascination to bear on the flora of the world is no accident: he describes how, though “There has been a revolution worldwide in attitudes towards the natural world in my lifetime […] [a]n awakening and an awareness of how important the natural world is to us all”, this hasn’t necessarily extended to people’s understanding of plants. It’s his hope that The Green Planet “will bring [this] home”. The series has therefore been consciously designed to push audiences toward greater appreciation for and understanding of plants, and of their crucial role for life on our planet.

“Over half the population of the world according to the United Nations are urbanised, live in cities, [and] only see cultivated plants” – meaning that the “parallel world [of plants,] on which we depend, […] [is] largely ignored” (at least, as he adds, for that urban part of our population). This is where developments in technology pay dividends: being able to “go into a real forest […] [and show] a plant growing with its neighbours, fighting its neighbours […], or dying […] brings the thing to life.” He hopes that being able to see plant behavior with a level of immediacy not possible without time-lapse “should make people say, ‘Good lord, these extraordinary organisms are just like us’ in the sense that they live and die, that they fight, […] [and] they have to learn to reproduce.”

The different rate at which plants live is brought home by a scene in which Attenborough returns to a creosote bush growing in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert. Featured in 1982’s The Living Planet, the plant had grown just a quarter of an inch during the subsequent four decades.

The continued existence of one specific bush is a little glimmer of one of those narratives of hope. Maintaining that hope allows us to entertain the possibility that a future can exist – can be created – where the broader natural world, including the plants that so fundamentally underpin it, is allowed to thrive, and not continue to be obliterated.

As Attenborough summarises, “Our relationship with plants has changed throughout history and now it must change again. We must now work with plants and make the world a little greener, a little wilder. If we do this, our future will be healthier, and safer, and happier. Plants are, after all, our most ancient allies, and together we can make this an even greener planet.”

Earth.fm is a completely free streaming service of 1000+ nature sounds from around the world, offering natural soundscapes and guided meditations for people who wish to listen to nature, relax, and become more connected. Launched in 2022, Earth.fm is a non-profit and a 1% for the Planet Environmental Partner.

Check out our recordings of nature ambience from sound recordists and artists spanning the globe, our thematic playlists of immersive soundscapes and our Wind Is the Original Radio podcast.

You can join the Earth.fm family by signing up for our newsletter of weekly inspiration for your precious ears, or become a member to enjoy the extra Earth.fm features and goodies and support us on our mission.

Subscription fees contribute to growing our library of authentic nature sounds, research into topics like noise pollution and the connection between nature and mental wellbeing, as well as funding grants that support emerging nature sound recordists from underprivileged communities.