Not long ago I took part in a BioBlitz, near my home in Vermont, in the northeastern US. If you’re unfamiliar with the concept, let me explain.

I first became aware of the concept of a BioBlitz while watching a documentary about the late, great biologist, EO Wilson, and his activities to help preserve Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique. He conducted a BioBlitz there, and even though most of the participants were local kids, they discovered dozens of new species in the process. The effort made a difference in bringing the park back to life following two Mozambican civil wars, resulting in the reestablishment of one of the most exceptional national parks in the world.

A BioBlitz is a geographically contained activity during which, for a single 24-hour period, participants do everything they can to identify as many different species as possible within a predefined geography.

BioBlitzes are typically attended by scads of volunteers—hopefully, lots of kids—along with professional scientists who lend their expertise to the search and identification process. They set up mist nets for birds and catch-and-release traps for small mammals; they analyze soil samples for bacteria and other microorganisms; they put up light traps for nocturnal insects; and they collect fungi, plants, insects, fish, reptiles, amphibians, and whatever other living things they can find. It’s a wild, chaotic process, and it often results in the discovery of at least one or two previously unidentified species.

I’m a writer and wildlife sound recordist, and I attended the BioBlitz in Vermont’s state capital, Montpelier, because I was curious about the process. I wasn’t disappointed: the level of wild enthusiasm among the kids was infectious, and the extent to which the volunteer scientists were willing to share their knowledge was heartwarming. And, I learned a lot.

A couple of days ago, I had one of those rare epiphanies while I was editing the recordings from a recent recording expedition. I was thinking about my experience in Montpelier, and it made me wonder: why had no one ever organized an AudioBlitz? in other words, instead of requiring physical evidence of a creature or plant to prove its presence, why not focus on sound? Granted, most plants don’t make sound, although the wind blowing across a prairie, or wind blowing flute-like across the tops of reeds torn to different lengths by marsh wrens, or trees creaking against one another, are ample evidence of some sonic reality that should be recorded.

But imagine what might happen if we were to send a group of kids into the wild with a team of experienced sound recordists and naturalists, not to find physical evidence necessarily of the presence of non-human life, but rather to experience its presence through the sounds it makes? They could be paired with experienced recordists and people with expertise in birdsong or the calls of insects or the voices of amphibians, sitting in their watery abodes, singing lustily and loudly about sex. Recorders and microphones could be made available by local recordists, and computers could be set up with analysis software (spectrograms, etc.) to assess each recorded sound for adherence, for example, to Krause’s Niche Hypothesis, which observes that different species call in different frequency ranges to avoid ‘stomping’ on each other while simultaneously singing. A plethora of smartphone apps, such as iBird, Dawn Chorus, Merlin Bird ID, and others, makes sound identification infinitely easier.

This idea isn’t entirely new. I love birds, but I don’t go out of my way to create lists of all the birds I hear in a year. I simply enjoy hearing them and identifying them when I can. But I have spent time with serious birders who are adept at what they call ‘ear birding.’ In other words, even though they can’t see that bird that’s calling, deep in the undergrowth, they know beyond a shadow of a doubt what it is, because they know its song as well as they know its plumage. So, in some ways, identification of species purely by sound is already being done on a large scale. But as far as I know, no one has ever organized an AudioBlitz.

Perhaps it’s time.

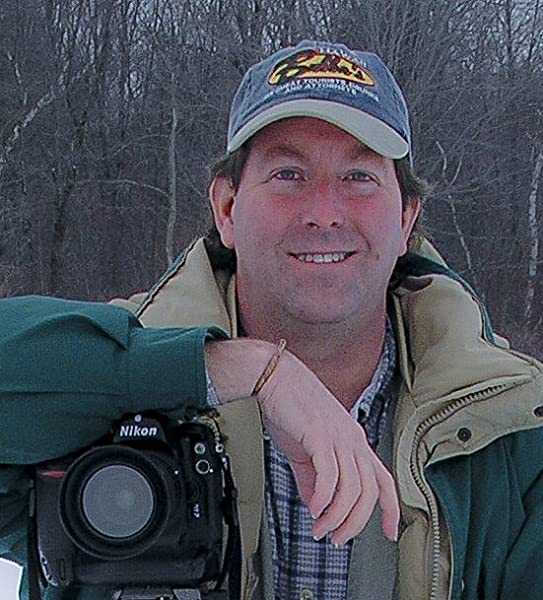

Dr. Steven Shepard is a Vermont-based professional author, photographer, audio producer, and educator with more than 40 years’ experience in the technology industry. He has written books and articles on a wide variety of topics – from history to wildlife sound recording – and worked in more than 100 countries. Steve is also the producer and host of the Natural Curiosity Project Podcast, and de facto representative in the US of the UK-based Wildlife Sound Recording Society.

Earth.fm is a completely free streaming service of 1000+ nature sounds from around the world, offering natural soundscapes and guided meditations for people who wish to listen to nature, relax, and become more connected. Launched in 2022, Earth.fm is a non-profit and a 1% for the Planet Environmental Partner.

Check out our recordings of nature ambience from sound recordists and artists spanning the globe, our thematic playlists of immersive soundscapes and our Wind Is the Original Radio podcast.

You can join the Earth.fm family by signing up for our newsletter of weekly inspiration for your precious ears, or become a member to enjoy the extra Earth.fm features and goodies and support us on our mission.

Subscription fees contribute to growing our library of authentic nature sounds, research into topics like noise pollution and the connection between nature and mental wellbeing, as well as funding grants that support emerging nature sound recordists from underprivileged communities.