An overview of animal rights around the world

This article explores animal rights with a focus on the current legal status of animals around the world – from wild species to pets and livestock – and some of the reasons why these protections are so limited.

Animal rights can be defined as “moral principles grounded in the belief that non-human animals deserve the ability to live as they wish, without being subjected to the desires of human beings”. Yet, except for situations in which they are considered human property, “in nearly every postindustrial country on Earth, from the USA to the UK to China to India” (as this map of national animal legislation demonstrates), animals have practically no legal protection which would enforce these principles.

Such a lack of legal rights for animals stems from an “assumption of humans’ superior moral worth”. This speciesist position, a “way of thinking [which] is embedded throughout our society in the ways that animals are talked about and treated”, includes the belief that humans are separate from and superior to the natural world. (In part, this belief is fuelled by the “Judeo-Christian doctrine […] used to justify the mistreatment of nonhuman animals”.)

Human exceptionalism of this kind has been historically justified by “a variety of standards […] [for] human uniqueness”, such as the idea that humans are the only species which “have sex for fun, solve social problems or develop familial bonds” – all of which have been disproved.

The presumption that animals are nonvocal, or otherwise unable to communicate, has also been used to support this position. However, this premise – which already willfully (and conveniently) overlooks the occasions in which animals can and do communicate to protest their circumstances, from the agitation displayed by cows separated from their newborn calves to the screams of animals skinned alive for their fur – is becoming increasingly spurious. For example, it has recently been shown that 53 species of vertebrates with lungs previously considered silent do in fact produce sound.

Why should we give animals rights?

We have exploited, abused, maimed (eg, through castration, dehorning, etc), killed, and otherwise subjugated animals since time immemorial. The argument for giving them legal rights is an acknowledgment of their entitlement, as sentient, feeling beings, to more humane treatment, dignity, and recognition and respect for these rights. While it would behove us to improve the way that we treat animals, for them having rights would mean “not be[ing] trapped, beaten, caged, artificially inseminated, mutilated, drugged, traded, transported, harmed and killed” for human profit.

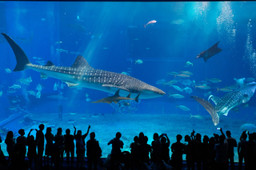

Other violations of animals’ rights include forced breeding (for food, or to produce pets for financial gain); impregnation to ensure milk production; being trained to perform (for example, in circuses); being raced; vivisection and having products tested on them; being hunted recreationally; being skinned for fur or leather, or plucked for their feathers; and being kept in captivity for our entertainment (whether domestically or in zoos).

It’s worth pointing out the difference between animal rights and animal welfare; animal welfare can be defined in a variety of ways (including high productivity; ie, according to their usefulness). Animal rights, on the other hand, supports their “moral worth independent of their utility to humans”. However, it is only by enshrining these rights in law that animals can be protected accordingly.

At the core of animal rights is animal autonomy (the right to choice). In the same way that, in many countries, human rights may be “constrained depending on social locations like race, class, and gender”, animal rights are inhibited by their exploitation by humans, and by our destruction of their habitats.

Are there any arguments against animal rights?

Supporters of animal rights say that we have no moral right to harm other sentient beings. It has even been argued that rights for animals would contribute to the dismantlement of “a biological hierarchy with European straight white males at the top”.

Counter-arguments (made by those who benefit from animal exploitation; factory farming alone is “a multi-billion-dollar industry”) claim that animals are not deserving of rights because they are not intelligent. Even if it were true that animals are unintelligent (as opposed to having different kinds of intelligence to humans), this perspective only makes sense if “we accept that [babies,] children and those with serious mental impairments do not have [or deserve] rights”.

Religion may also be used to justify human dominance over animals, or even the idea that rights for animals “would diminish [rather than enhance] human rights and undermine our ‘special’ role in the world”.

More broadly, tradition and habit plays a role in people’s unwillingness to move beyond the current status quo: ‘We’ve eaten like this since we were hunter-gatherers!’ Yes, but we also used to live in caves and no-one’s contesting the benefits of progress in that context.

Concerns about the healthiness of not eating meat is a common stumbling block, even for individuals who would prefer to not personally contribute to farming practices which are harmful to animals (and to the environment). However, plant-based diets are linked to the reduction of “risk of heart disease, strokes and type 2 diabetes […] [and] can […] lower […] blood pressure, reduc[e] blood cholesterol and promot[e] a healthy bodyweight”.

This is not to say that the “exclusion of animal products […] necessarily equate[s] to a healthy diet” (highly processed products like cookies, French fries, or ice cream, which contain refined carbohydrates and large amounts of sugar and salt can be as unhealthy as any ultra processed foods, even if they are vegan or vegetarian). Yet it is also not true that plant-based diets are unable to provide the nutrients found in meat or dairy products.

Plant-based sources of protein include tofu, lentils, beans, nuts and nut butters, seeds, and quinoa, while though it can be more difficult “to get [certain nutrients] through a vegan diet” (eg, vitamin D, vitamin B12, iodine, selenium, calcium, and iron), this is not impossible. Calcium, for example – mainly obtained by non-vegans from dairy foods – can also come from green, leafy vegetables, sesame seeds and tahini, and dried fruit (among other sources). Iron is present in sources including pulses, wholemeal bread and flour, and nuts; vitamin B12 is found in yeast extract (like Marmite); and omega-3 fatty acids are obtainable from chia and shelled hemp seeds and walnuts. In addition, fortified foods or supplements may also be helpful for non-meat-eaters.

A balanced plant-based diet also provides “essential nutrients that you cannot get from other foods […] [such as] vitamins and minerals, phytochemicals and antioxidants”, which reduce inflammation; help to maintain a healthy weight; lower cholesterol, stabilize blood sugar, and reduce the risk of cancer; and provide higher quantities of beneficial “vitamins C and E, dietary fiber, folic acid, potassium, and magnesium”.

What are the benefits to animal rights?

Aside from the incontrovertible benefits to animals’ welfare, were these rights adopted, positive outcomes on a broader scale would include:

- Farms (including factory farms, or concentrated animal feeding operations [CAFOs]) and abattoirs becoming obsolete due to the cessation of breeding animals for food, milk, or eggs. A blanket adoption of a vegan lifestyle, with its corresponding reduction in the consumption of animal fats and protein, would also reduce expenditure on treatment for heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension, providing a concomitant improvement to the economy

- Reduction of deforestation due to less land being required for farming, as well as reduced ill effects on the environment and wildlife caused by agriculture, and a reduction in contributions to climate change. A population of vegans could be supported by much less land

- Putting a stop to bottom-trawling fishing, halting “the clear-cutting of corals that can be thousands of years old”

- Animal skins no longer being used for clothes or shoes (pineapple leather is just one viable alternative to toxic tanneries).

Adopting animal rights would also redress “the perception of animals as being unthinking, unfeeling beings [which] justifie[s] using them for human desires”. What scientific analysis is steadily showing – that animals, including those which we use as food or whose skins we use as clothing, “possess more cognitive complexity, emotions, and overall sophistication than has long been believed” – means that we can no longer claim ignorance of their pain or the impacts of our behavior upon their psychology.

Our obliviousness to other animals’ suffering has created an Earth where “livestock make[s] up 62% of the world’s mammal biomass […] and wild mammals […] [account for] just 4%”, and we are driving an inconceivable loss of species “between 1,000 and 10,000 times higher than the natural extinction rate”.

What is the legal status of animal rights?

Animal rights have only been recognised in a handful of countries. In the UK, the Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act was passed in 2022, meaning that animal sentience is now recognised in law – and includes wild animals, which previous bills related to animal welfare have not. Though the act does not grant animals autonomy, it nevertheless marks “a watershed in the movement to protect animals—officially recognizing their capacity to feel and to suffer, and distinguishing them from inanimate objects”.

The nearest equivalent in the US, the Animal Welfare Act, excludes numerous species (including farmed animals), and doesn’t acknowledge animals’ “ability to feel pain and suffer”. Perhaps for this reason, there are currently almost 50,000 ‘animal-focused nonprofit organizations’ in the country. The modern animal rights movement in the US is indebted to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), which was founded in 1866 by diplomat and activist Henry Bergh, initially to “focus […] on efforts for horses and livestock”. Today, the ASPCA continues to confront “challenges facing animals […] [by] providing vital veterinary care, responding to disasters, pioneering adoption and behavioral rehabilitation programs, conducting critical animal welfare research, training law enforcement and shelter professionals, and advocating for more effective laws”.

Were future laws to go further than simply “shielding animals from cruelty”, by giving them autonomy, animal rights which could be protected might include the right to not be used as food; to not be hunted; to have their habitats protected; and to not be bred.

However, it is worth speculating whether, in this model, provision would be made for Indigenous peoples who traditionally rely on animals (such as the Inuit use of sled dogs, or the relationship between Mongolians and their horses), and whether, poorly applied, such legislation could inhibit their role as “the world’s biggest conservationists”.

What is the future for animal rights?

This question is complicated by a lack of clarity around the current reality of different countries’ treatment of animals. Different rankings produce wildly differing pictures of the best and worse. In 2021, insurance company the Swiftest created an international Animal Rights Index, which considered factors including “recognition of animal sentience […] [,] fur-farming bans, […] pesticide use and meat consumption”; on this basis, it named Luxembourg, the UK, and Austria as the top three ‘best countries for animal rights’, with Iran, Vietnam, and China taking up the rear (out of the 67 countries surveyed). The US came in at number 40. (British tabloid The Sun gleefully counted down the most heinous animal rights abuses from the worst countries on the list – proceed with caution.)

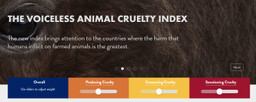

On the other hand, the Animal Cruelty Index created by Voiceless, an Australian animal protection organization, ranks Australia and Belarus as joint ‘cruelest’, with the US at number two. India and Tanzania were tied for best animal welfare, followed by Kenya. As Sentient Media points out in its assessment of these results, “rankings are made by people with specific viewpoints […] [and] tend to leave out important social contexts and histories […], like how more powerful countries have taken advantage of less wealthy countries, and the dispossession and colonization of Indigenous people and lands, which have helped to shape diets and farming systems”.

This muddies the (perhaps naive) idea that, where industrial farming has become the norm in the Global North, countries in the Global South might have a cuddlier relationship with the working animals which are still a day-to-day part of people’s lives. Sadly, donkeys in Ethiopia “abandoned or left to hyenas” when too sick to work, or “a supermarket for illegal wildlife trafficking” in Vietnam, tell a different story.

Animal rights are complex: Where do we go from here?

Animal rights is “a multi-issue topic related to many different discussions about rights and justice”, which is to say that it is a complex (not to say contentious) issue containing multitudinous interpretations and a wide variety of repercussions through all aspects of human society, with additional variations between countries and cultures.

Such a multifaceted topic can be difficult to get to grips with, much less to establish clarity about what an individual can do to benefit animal rights. However, many figures in the English-speaking world can help illuminate these issues. Activist and vegan educator Ed Winters, for example, has written This Is Vegan Propaganda (and Other Lies the Meat Industry Tells You) and How to Argue with a Meat Eater (and Win Every Time), released Land of Hope and Glory, a documentary film which “show[s] the truth behind UK land animal farming”, and co-founded Surge, “a creative non-profit striving to create a world where compassion towards all non-human animals is the norm”.

Similarly, moral philosopher Peter Singer authored the influential Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals in 1975 (“fully rewritten and entirely updated to reflect the pressing problems of today” as Animal Liberation Now in 2023), and co-founded Animals Australia (originally the Australian Federation of Animal Societies), which “works to protect the most vulnerable and abused animals”. His opinions on flexible veganism, conscientious omnivores, cultured meat, and even medical experimentation on humans rather than animals are well worth engaging with, as is his persuasive critique of speciesism:

“Just as we accept that race or sex isn’t a reason for a person counting more, I don’t think the species of a being is a reason for counting more than another being. What is important is the capacity to suffer and to enjoy life. We should give equal consideration to the similar interests of all sentient beings. […] Instead of defending the idea that all humans have rights but no animals do, we should recognise that many things we do to animals cause so much pain and yet are so inessential to us that we ought to refrain.”

So how can I help to increase animal rights?

We may not all have capacity to lobby the relevant authorities in support of increased animal rights, but, like so many issues, small daily actions or changes to our regular behavior can add up to a cumulative change. Perhaps consider fostering an animal in need, teaching your children to respect animals, donating to relevant charities, fundraising for organizations like the Humane Society of the United States, and choosing not to buy products tested on animals.

There is enormous room for improvement worldwide – though the failings of supposed world leaders like China and US are particularly glaring – but change will only come through the commitment of those dedicated to improving standards for our more-than-human cousins.

Earth.fm is a completely free streaming service of 1000+ nature sounds from around the world, offering natural soundscapes and guided meditations for people who wish to listen to nature, relax, and become more connected. Launched in 2022, Earth.fm is a non-profit and a 1% for the Planet Environmental Partner.

Check out our recordings of nature ambience from sound recordists and artists spanning the globe, our thematic playlists of immersive soundscapes and our Wind Is the Original Radio podcast.

You can join the Earth.fm family by signing up for our newsletter of weekly inspiration for your precious ears, or become a member to enjoy the extra Earth.fm features and goodies and support us on our mission.

Subscription fees contribute to growing our library of authentic nature sounds, research into topics like noise pollution and the connection between nature and mental wellbeing, as well as funding grants that support emerging nature sound recordists from underprivileged communities.