Acoustic ecology and the World Soundscape Project

What is acoustic ecology?

The discipline of acoustic ecology (or soundscape studies) originated from the work of the World Soundscape Project (WSP).

The WSP’s founder, R. Murray Schafer, wrote a key text on the subject in 1977: The Tuning of the World. In it, he defines ecology as “the study of the relationship between living organisms and their environment”, with acoustic ecology being “the study of sounds in relationship to life and society”. He expanded that, “Its particular aim is to draw attention to imbalances which may have unhealthy or inimical effects.”

To Schafer, acoustic ecology was fundamentally interconnected with acoustic design, a way to pursue “principles by which the aesthetic quality of the acoustic environment or soundscape may be improved”, with that soundscape regarded “as a huge musical composition, unfolding around us ceaselessly”.

Part of Schafer’s motivation for developing this field of study came from his conviction that a visual understanding of the world had come to predominate over engagement through hearing. On the basis of his own experience as a teacher, he believed that this “eye culture” (as J.E. Berendt described it in his exploration of hearing, The Third Ear) extended to a decline in children’s capacity for listening. He believed this lack of “sonological competence” was characterised by an inability to consciously take in non-musical sounds heard throughout the day.

Who was R. Murray Schafer?

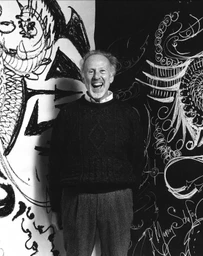

The self-declared father of the discipline, Schafer (1933-2021) was a prolific composer and writer – as well as an educator and environmentalist – who originally dreamed of being a painter. His multihyphenate outlook is imprinted on acoustic ecology itself, which straddles “acoustics, architecture, linguistics, music, psychology, sociology and urban planning”.

Largely self-taught after dropping out of formal education, an environment he considered limiting, Schafer instead left his native Canada to spend much of the 1950s in Austria and England. In the 60s, having returned to Canada, composition and teaching – including attempts to promote “sensory awareness” – would remain constant throughout the rest of his life.

His work as a composer drew on sources as varied as Homer, Herman Melville, Ezra Pound, verse by Bengali polymath Rabindranath Tagore, and The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Certain compositions were directly influenced by his own acoustic-ecological thinking, with pieces that drew on the structure of ocean waves or traffic noise. Similarly, his “natural-environment works” engage with the dictums of acoustic ecology by positioning musicians throughout natural environments (say, around a lake) – a form which culminated in “theatrical musical pageant” Apocalypsis, which requires a minimum of 500 spatially distributed performers.

Schafer chose to live in rural locations, away from urban “sonic sewers”; in these settings, he worked with local communities, including founding the Maynooth Community Choir. In working at this level, Schafer was advocating for an engagement with the local in a way which echoed the mentality of acoustic ecology, in which any and all environments are equally worthy of study and improvement.

What was the World Soundscape Project?

As a result of his interests, Schafer founded the WSP in the early 70s, at Simon Fraser University (SFU), British Columbia, Canada, with an education- and research-based remit. Aims included increasing public awareness of issues around acoustic ecology; documenting the sounds present in particular environments; and the establishment of acoustic design as a counteragent to noise pollution.

The WSP’s output included field recordings made in both Canada and Europe; books including The Tuning of the World and other titles by Schafer; project documentation, such as A Survey of Community Noise By-Laws in Canada (1972); and a 10-hour radio series documenting the Canadian soundscape.

It was hoped that, eventually, the WSP would be able to create a balance “between the human community and its sonic environment”. To this end, listening and “ear-cleaning” practices, including “soundwalks” – a walking meditation where a high sonic awareness is maintained – were designed to increase individuals’ consciousness of the sounds around them. By prompting engagement with the realities of contemporary soundscapes, listeners were intended to gain awareness of their part in these soundscapes’ creation, and therefore appreciate their responsibility towards them.

What are the principles of acoustic ecology?

The World Soundscape Project worked from the basis that any given soundscape (or sonic environment) is a representation of how that environment is perceived by listeners within it. Soundscapes are themselves influenced by human behaviours. As a combination of all sound within a particular location, soundscapes may therefore comprise natural sounds as well as those from social and technological sources. As these sounds change, so does the ecology of the soundscape.

Acoustic ecology addresses the maintenance of soundscapes’ “acoustic balance” and ways to improve their perceived quality. An imbalance between listening and sound-making would impair the quality of a soundscape; for example, if human sounds overwhelm natural sounds.

Recordings by the World Soundscape Project

The first comprehensive field study by the WSP, The Vancouver Soundscape derived specifically from F. Murray Schafer’s concern at the effects of noise pollution on the sonic environments of the city. A course he was teaching on the subject at SFU attracted a group which shared these anxieties. In 1972, having secured funding, this group made recordings of Vancouver’s sonic environments and “soundmarks” (sounds particularly memorable for those within their locality), some of which can be heard below:

In a 2013 blog post, the London-based British Library shared a selection of field recordings subsequently made by the WSP in Northern Europe, in 1975. Its intention was to create an aural snapshot of village life; findings were published as a book, Five Village Soundscapes, with recordings backed up by documentation including isobel maps (plotting variations in sound pressure) and charts showing the locations of pitches and hums in the environment.

Material gathered by WSP members, touring in a Volkswagen campervan, includes:

- The bells of Storkyrkan church; Stockholm, Sweden

- A blacksmith at work; Bissingen, Germany

- A fish auction; Nogent-le-Retrou, France

- Street sounds; Cembra, Italy

- A chorus of frogs; Rennes/Montreuil, France.

What is the legacy of the World Soundscape Project?

The WSP’s legacy continues through relevant courses still taught at SFU; composers make work jumping off from approaches used by Schafer; and, in 1993, the World Forum for Acoustic Ecology (WFAE) was formed to continue the Project’s drive for soundscape awareness, but on an international scale.

With various different emphases, a range of academics, musicians, and composers have expanded into the present day upon foundations laid by the WSP. For example, professor emeritus and electroacoustic composer Barry Truax (a former member of the WSP); Hildegard Westerkamp, activist and soundscape composer (and founder member of the WFAE); video and sound lecturer David Murphy; and researcher and instructor Milena Droumeva.

Certain of the WSP’s work has been revisited. A follow-up to The Vancouver Soundscape, titled Soundscape Vancouver 1996, created compositions from new recordings of similar environments 23 years on (the track ‘Pacific Fanfare’, by Barry Truax, can be heard here). Almost 15 years later, a Finnish study, Acoustic Environments in Change, expanded upon Five Village Soundscapes with further recordings at these locations (as well as at a sixth village, in Finland).

By comparing contemporary soundscapes with those documented by the WSP itself, new work within the field of acoustic ecology not only allows methodologies to be refined and updated, but stakes a claim for the continued relevance of projects of this type – both in terms of anti-noise legislation, and more broadly.

Given the ongoing and escalating climate crisis, the importance of what R. Murray Schafer kick-started will only increase. Though less tangible than the loss of habitats or species, what acoustic ecology has to teach us will continue to be deeply significant for as long as human impacts adversely affect the biosphere.

Earth.fm is a completely free streaming service of 1000+ nature sounds from around the world, offering natural soundscapes and guided meditations for people who wish to listen to nature, relax, and become more connected. Launched in 2022, Earth.fm is a non-profit and a 1% for the Planet Environmental Partner.

Check out our recordings of nature ambience from sound recordists and artists spanning the globe, our thematic playlists of immersive soundscapes and our Wind Is the Original Radio podcast.

You can join the Earth.fm family by signing up for our newsletter of weekly inspiration for your precious ears, or become a member to enjoy the extra Earth.fm features and goodies and support us on our mission.

Subscription fees contribute to growing our library of authentic nature sounds, research into topics like noise pollution and the connection between nature and mental wellbeing, as well as funding grants that support emerging nature sound recordists from underprivileged communities.